Branching

One can initialise a new repository and set the main branch name as follows:

git init -b mainBranchName

One can rename a branch later with:

git branch -m oldName newName

Branches can be named with / to mimix Unix pathnames, and subsequently form a useful way to organise branches. For example

- bug-fix/ticketX

- bug-fix/ticketY

One can view a list of commits for multiple branches using a wildcard * as:

git show-branch 'bug-fix/*'

One can create a new branch and then checkout the new branch with:

git checkout -b newBranchName

The HEAD pointer

The HEAD pointer represents the current reference point along a current branch and by default points to the latest commit.

There is only one HEAD per repository, as such.

One can “check out” an existing branch and this by default, will set the HEAD pointer to the latest hash along the existing branch. It is possible to detach the HEAD pointer to some preceding commit hash. Git commands generally assume the point of view of the HEAD pointer.

Stashing and carrying updates to a different branch

A given developer can only have one active branch at a time. Before checking out other branches, developer would need to commit changes. There are cases where this is not desirable (changes may be expected to pass tests before being committed) while also noting that the current changes should not simply be discarded. In these circumstances, Git provides a way to stash changes (sometimes more than once) and then return to them later. Use git stash -m "stash comment".

Developers can also merge uncommitted changes from the current branch to a desired branch following a git checkout targetBranchName command. This is not the same as merge of branches but actually an example of a three-way merge.

Listing branches

Use the following to view local (temporary) branches:

git branch

The following will show remote (permanent) branches:

git branch -r

Finally, the following shows both local and remote branches:

git branch -a

As shown above, use git show-branch to list commits of the current branch.

Checking out specific commits

One can checkout a specific commit in one of several ways:

- by hash value (SHA)

- by tag name

- by reference to the HEAD pointer, with ^ e.g.

git checkout HEAD^^^to checkout a commit three behind HEAD (this assumes that the path to the third commit is unambiguous) - by reference to the tip of the branch (latest commit) with ~ e.g.

git checkout branchName~4to checkout a commit four behind the tip (again, assumes an unambiguous path)

Either way, this detaches the HEAD pointer from the tip of the branch. This effectively results in a HEAD that is not part of the branch anymore, and so any subsequent commits, while permitted, will not be associated with any branch. Consequently, when one tries to checkout the tip of the branch later, the aforementioned commits are unreachable (they do not belong to any branch).

To make the commits reachable, one must start a new branch when the HEAD is detached, before committing changes. It is also possible to tag a (dangling) commit and then be able to access the commit later via the tag.

Eventually, any commits that are not tagged or part of a branch are disposed via Git’s garbage collection.

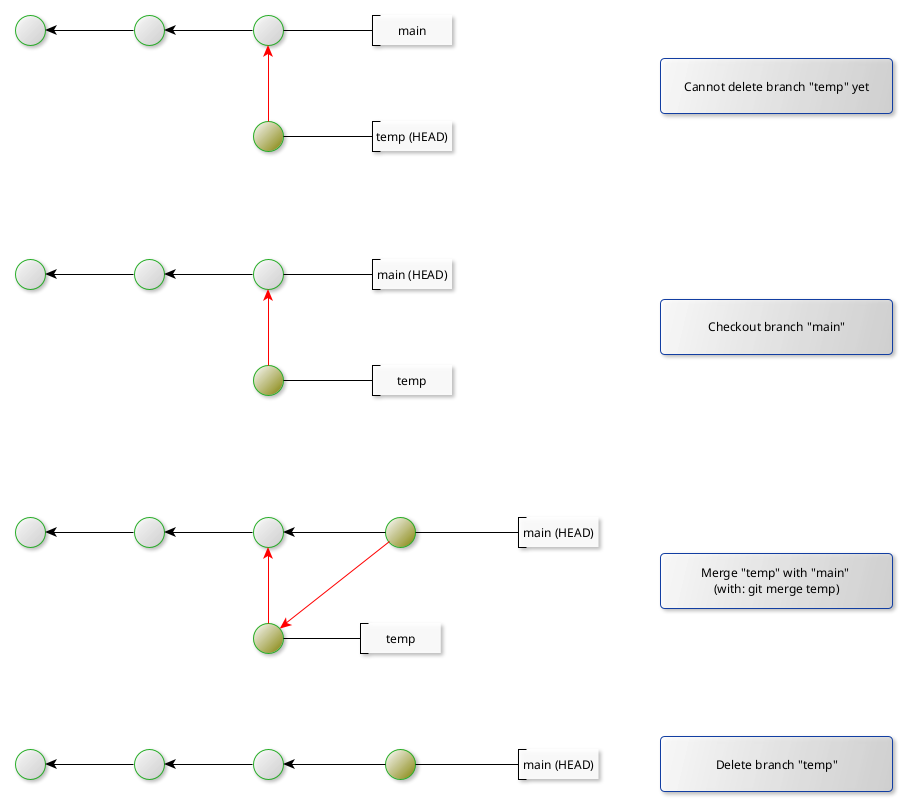

Deleting branches

This is typically done locally, when short-lived bug fix or feature branches (not expected to be part of the remote repository) are deleted.

Revisiting the idea of unreachable commits again, Git safeguards users from deleting branches if it means that any commit is left unreachable. This is actioned if one runs:

git branch -d branchName

Some commits are part of more than one branch, so in such cases it is possible to delete one of the branches. In other cases, Git will by default prevent users from deleting branches.

If a situation arises whereby a commit would become unreachable, then in order to delete the branch, one would need to either:

- checkout a (different) branch that also has the commit (that should not be deleted) and then proceed to delete a different branch that also has the commits

- get the commits over to an existing branch via a merge, before deleting the branch

To force Git to delete a branch (knowing the consequences) then use:

git branch -D branchName

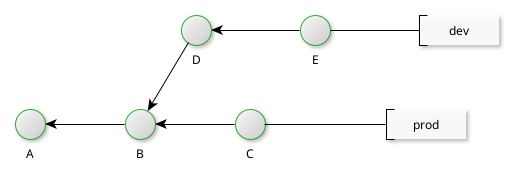

Commit graphs

On the subject of branching, now seems appropriate to outline commit graphs. These represent the relationship between each commit across branches.

The scheme is represented by a DAG diagram (highlighted by the section Internals), usually in a more simplified manner. Only the commit nodes are illustrated, the reader can then assume that the related trees, blobs and tags (where applicable) are in effect but hidden.

The above DAG diagram is often assumed to portray time from left to right, with the slant of the edge (from B to D in this case) attempting to show that commit D was created as the new branch dev. Many DAG diagrams do not use arrow heads and therefore the parent commit of a given commit is implied.

In the above scenario, the project state from the tip of dev only considers commits A, B,D and E. Similarly, the project state according to branch prod is defined by commits A, B and C only.

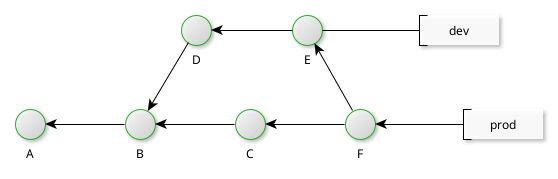

Once can merge dev with prod as shown below.

Now the prod branch is defined by all commits shown.

Commit ranges

One can formalise methods to deduce where commit reside through a commit range operation. The operator is denoted by two periods .. and written as:

notInThisBranch..inThisBranch

or sometimes as

start..end

To deduce this from a commit graph, simply start at the tip of branch start and work back to its parent commits, added each commit to a set.

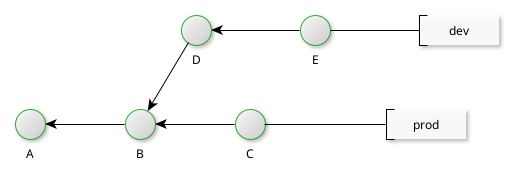

For example, the commit range of dev..prod for the following commit graph would be the set {C}. Starting at commit E and noting the forward slant of the divergence of the dev branch, one should see that commit C is in prod but not in dev:

Similarly, the commit range prod..dev is the set {D, E}.

This can also highlight that the edge between commits B and D is not part of the branch dev. The dev branch effectively only has one edge, that between commits D and E.

From a Git standpoint, one can show the commit logs (messages) of a given commit range with either command:

git log ^prod dev

git log prod..dev

Basically, this lists commits logs (and clearly, commits) not in prod but in dev. Put another way, prod..dev gives all commits that are reachable from the tip of dev but without any commit present in up to and including the tip of prod.

This pattern may prove helpful when seeing what is yet to be merged from the dev branch (to the prod branch).

Commit ranges also find use when passed as parameters for git diff and git log commands.